Meniere’s Disease was first described by Prosper Meniere in 1861. Dr. Meniere was a French physician who focused on diseases of the ear after securing the position of physician-in-chief at the Institute for Deaf-Mutes in Paris. Dr. Meniere died in 1862 at the age of 63.

Meniere’s disease is a disease of the inner ear, which includes the entire labyrinth (cochlea and semicircular canals). The cochlea is the organ of hearing. The semicircular canal/vestibule is the organ of balance. It was probably Dr. Meniere who first recognized that “vertigo and hearing loss commonly occur together with inner ear disease (1).”

The Eustachian tube is also an important part of the inner ear, and this discussion will elaborate on the possible role of the Eustachian tube in Meniere’s disease.

The various canals of the inner ear, or labyrinth, contain a fluid known as endolymph. The endolymph pressure normally remains constant. For unknown reasons, increases in the endolymphic pressure may cause dilation and distention of the labyrinth, a condition known as “hydrops,” or “endolymphatic hydrops.” Although there are clearly those with hydrops that do not have Meniere’s disease, most patients with Meniere’s disease do have hydrops.

Meniere’s disease is characterized by attacks of dizziness, nausea, vomiting, ringing in the ears (tinnitus), a feeling of fullness or pressure in the ear, and fluctuating hearing loss with occasional deafness. A typical attack of Meniere’s disease is preceded by fullness in one ear. Hearing fluctuation or changes in tinnitus may also precede an attack. A Meniere’s episode generally involves severe vertigo (spinning), imbalance, nausea and vomiting. The average attack lasts two to four hours. Following a severe attack, most people find that they are exhausted and must sleep for several hours. There is a large amount of variability in the duration of symptoms.

In Meniere’s disease, the attacks of vertigo can be severe, incapacitating, and unpredictable. Some patients experience “drop attacks” where a sudden, severe attack of vertigo or dizziness causes the patient to fall.

Meniere’s disease is a disease of middle age. The age of onset is usually around age 40. The disease is very rare in children. Meniere’s disease is initially unilateral, but becomes bilateral over a period of 5–30 years in about half of patients.

Meniere’s attacks often occur in clusters. Several attacks may occur within a short period of time. However, years may pass between episodes. Between the acute attacks, most people are free of symptoms or note mild imbalance and tinnitus.

In most patients with Meniere’s disease, the underlying cause is unknown. It is most often attributed to viral infections of the inner ear, head injury, allergy, or autoimmune inner ear disease. Importantly, especially for this discussion, is understanding that stress has been identified as a factor that can bring on an attack of Meniere’s disease. This suggests that increased sympathetic tone is physiologically an aspect of Meniere’s disease.

Meniere’s disease has a severe impact on people’s lives. In acute episodes, Meniere’s disease is one of the most debilitating diseases experienced by people who survive any illness. Meniere’s disease may persist for decades, and it is generally a chronic disease after its first middle age episode.

Harry Lee Parker, MD (d. 1959), professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, describes a 50-year old patient with Meniere’s disease as follows (2):

I have a man here who complains of dizziness. This strikes him where and when he least expects it. The world revolves around him; he is nauseated and vomits, and he falls down prostrate. His life is spent in dread of such an occurrence, and he can not depend on his coming or his going.

For ten years he has been annoyed by a sound in his right ear. It is high-pitched and is compared to that of a water mill. Hearing in the same ear has been failing, so that he now uses a telephone receiver altogether on his left side. Two years before he had his first attack of vertigo. This was terrific! At his place of business he was struck as if by lightning, and fell on his face amongst his papers and vomited all over them. He was carried home and put to bed, where he lay for twenty-four hours with his eyes tightly shut. He did not dare to move trunk or limb. Each time he opened his eyes the room swam around him, and he vomited anew and retched thereafter incessantly.

He recovered from this attack by being quiet and motionless, for a week, and was free from any trouble for three months. He regarded this as a single episode never to be repeated. At that time the iron had not entered his soul.

Remorselessly, however, the attacks of vertigo, nausea and vomiting recurred and kept occurring. These attacks of ringing in his ears, nausea and dizziness come more frequently, but as a recompense are less severe and of shorter duration. The noise in his ear is greater before an attack of vertigo, and the deafness is more marked.

The psychologic side is paramount here. Displacement in space is a grievous affliction. Deafness can be adjusted to, tinnitus can be ignored, but to be suddenly distorted, avulsed and misplaced in the old, well-known, solid, happy earthly medium is something that produces a nervous shock, invites a neurosis. An attack of vertigo is more demoralizing than a headache. Pain is in one’s being, but vertigo is a translation to another sphere.

As noted above, the Eustachian tube (also known as the pharyngotympanic tube and/or the auditory tube) is an important part of the inner ear. The Eustachian tube links the nasopharynx to the middle ear. It extends from the middle ear to the lateral wall of the nasopharynx.

Normally the human Eustachian tube is closed, but it can open to let a small amount of air through to equalize the pressure between the middle ear and the environment. Muscles control this opening event.

Another important function for the Eustachian tube is to drain mucus from the middle ear. Chronic muscular contractions, upper airway infections or allergies can cause the Eustachian tube to become swollen, impairing normal function.

Two of the muscles associated with the function of the Eustachian tube are innervated by the motor (mandibular) division of the fifth cranial nerve (trigeminal). They are the tensor tympani and the tensor veli palatini. Abnormal tone in these muscles may cause dysfunction of the Eustachian tube, disrupting normal atmospheric pressure regulation and impairing inner ear mucus drainage. These functions can be related to Meniere’s disease.

There is evidence that a contributing component to the pathophysiology of Meniere’s disease is altered biomechanical function of the cervical spine, especially the upper cervical spine. Supporting studies for a cervical-Meniere’s relationship can be found in the literature for nearly half a century:

- In 1961, physician Karel Lewit, MD, published a study titled (3):

Meniere’s Disease and the Cervical Spine

In this article, Dr. Lewit notes that many cases of Meniere’s disease are related to biomechanical problems of the upper cervical spine.

- In 1962 orthopedic surgeon Murray Braaf, MD, and neurosurgeon Samuel Rosner, MD, published a study titled (4):

Meniere-like Syndrome Following Whiplash Injury of the Neck

In this study, the authors reviewed 200 cases of cervical trauma in which the patients appeared to have developed symptoms consistent with Meniere’s disease. In their article, Drs. Braaf and Rosner state:

Meniere’s syndrome may be part of the cervical syndrome in much as the symptoms of equilibratory disturbances are very much the same in both instances and are due to reflex stimulation of the sympathetic nerve supply to the inner ear and to the eye.

Importantly, these authors both discuss cervical spine biomechanics as a component of Meniere’s disease and attribute the neurophysiologic lesion to the sympathetic nervous system. As we will see, other contemporary authors will publish similar pathophysiologic observations.

- In 1971, the authoritative text written by Georg Schmorl (d. 1932) and Herbert Junghanns (d. 1986) The Human Spine in Health and Disease (5), reference Lewit (3) in noting that Meniere’s disease is a “disturbance originating in the cervical spine.” Georg Schmorl was a German physician and pathologist. Herbert Junghanns was the Chief of the Occupational Accident Hospital, Surgical Clinic, and Head of the Institute for Spinal Column Research, in Frankfurt, Germany.

- In 1998, Howard Vernon, DC, published his book, Upper Cervical Syndrome (6). Again referencing Lewit (3), Dr. Vernon states:

Although the classic consideration is that this disease [Meniere’s] is a form of labyrinthitis, a large majority of cases are related to functional disturbances of the upper cervical spine.

- In 1996, Swedish dentists Assar Bjorne and Goran Agerberg published an article in the Journal of Orofacial Pain titled (7):

Craniomandibular disorders in patients

with Menière’s disease: a controlled study

In their study, Drs. Bjorne and Agerberg compared the frequency of signs and symptoms of craniomandibular disorders and dental conditions in thirty-one patients diagnosed with Meniere’s disease and compared them to a control population of thirty-one subjects. Both groups were subjected to a screening of their symptoms with a self-administered questionnaire and to a routine stomatognathic examination. The function of the masticatory system was further calculated for both anamnestic dysfunction and clinical dysfunction state. Clinical symptoms of craniomandibular disorders such as pain in the face or jaw; pain on movement of the mandible; fatigue of the jaws; and pain located in the vertex area, the neck/shoulder area, and the temples all occurred significantly more often in the Meniere’s patient group. Findings at the clinical examination included a statistically higher frequency of tenderness to palpation of the masticatory muscles, the temporomandibular joint, and the upper part of the trapezius muscle in the patient group compared to that of the control group. The authors concluded that there is a much higher prevalence of signs and symptoms of craniomandibular disorders in patients diagnosed with Meniere’s disease than in the general population.

It is important to recall that the upper cervical spine and the craniomandibular joint function interdependently (8). In fact, in this study, Drs. Bjorne and Agerberg state:

Palpation of the upper part of the trapezius muscle in the area of the atlas, the axis, and the third cervical vertebra showed statistically significant differences between the two groups.

Without doubt, the great soreness at palpation in the patient group express signs of neck disorders and correlates well with their symptoms.

- In 1998, Drs. Bjorne and Agerberg and physiotherapist Agenta Berven published a study in the Journal of Craniomandibular Practice (Cranio) titled (9):

Cervical signs and symptoms in patients

with Meniere’s disease: a controlled study

This study compared the frequency of signs and symptoms from the cervical spine in 24 patients diagnosed with Meniere’s disease and 24 control subjects. Symptoms of cervical spine disorders, such as head and neck/shoulder pain, were all significantly more frequent in the patient group than in the control group. Most of the patients (75%) reported a strong association between head neck movements in the atlanto-occipital and atlanto-axial joints and that they triggered attacks of vertigo. Also, 29% of the patients could influence their tinnitus by mandibular movements. Signs of cervical spine disorders, such as limitations in side-bending and rotation movements, were significantly more frequent in the patient group than in the control group. Tenderness to palpation of the transverse processes of the atlas and the axis, the upper and middle trapezius, and the levator scapulae muscle were also significantly more frequent in the patient group. The study shows a much higher prevalence of signs and symptoms of cervical spine disorders in patients diagnosed with Meniere’s disease compared with control subjects from the general population. These authors concluded:

The results of this study show that patients diagnosed with Meniere’s disease have signs and symptoms of cervical spine disorder that are much more severe than does the general population.

Patients diagnosed with Meniere’s disease report that a shifted posture and tension could trigger their vertigo. Most of the patients also reported an association between head/neck movements in the atlanto-occipital and the atlanto-axial joints that triggered vertigo attacks. Some also reported that they could influence their tinnitus by mandibular movements.

Patients with Meniere’s disease have more limitations in neck mobility, both in rotation and side-bending movements.

- In 1999, Burkhard Franz and colleagues from the Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology of the University of Melbourne and the Tinnitus Research and Balance Clinic, Victoria, Australia, published a study in the International Tinnitus Journal titled (10):

The cervicogenic otoocular syndrome:

a suspected forerunner of Meniere’s disease

In this study, the authors, over a period of 4 years, observed 420 patients with fullness in the ear, episodic vertigo, fluctuating hearing, and tinnitus. They persistently found a relationship between Meniere’s disease signs and symptoms, eustachian tube dysfunction, and a functional disorder of the upper cervical spine. They referred to this combination of signs and symptoms as “cervicogenic otoocular syndrome.” These patients often responded favorably to mechanically based conservative management. They concluded:

The cervicogenic otoocular syndrome is suspected to be a forerunner of Meniere’s disease.

In January 2003, Drs. Bjorne and Agerberg published another study in the Journal of Craniomandibular Practice (Cranio) titled (11):

Symptom relief after treatment of temporomandibular

and cervical spine disorders in patients

with Meniere’s disease: a three-year follow-up

This study describes the coordinated treatment of temporomandibular disorders (n = 31) and cervical spine disorders (n = 24) in patients diagnosed with Meniere’s disease. The study patients were followed for three years with examinations every six months. At each follow-up, their symptoms were evaluated using self-administered questionnaires and visual analog scales.

The results of the coordinated treatment showed simultaneous decreases in the intensities of vertigo, nonwhirling dizziness, tinnitus, feeling of fullness in the ear, pain in the face and jaws, pain in the neck and shoulders, and headache that were both longitudinal and highly significant. Significant longitudinal reductions in the frequencies of vertigo, nonwhirling dizziness, and headache were also reported by the patients as well as a complete disappearance of pain located in the vertex area. A significant relief of temporomandibular disorder symptoms and a decrease in nervousness was also achieved. The results showed that a coordinated treatment of temporomandibular disorder and cervical spine dysfunction in patients with Meniere’s disease is an effective therapy for symptoms of this disease. The results also suggested that Meniere’s disease has a clear association with temporomandibular disorder and cervical spine dysfunction and that these three ailments appeared to be caused by the same stress, nervousness, and muscular tension.

Once again, these authors state: “the movements of the mandible and the upper cervical joint (C0/C1) constitute an integrated motor system.” This is an important therapeutic biomechanical consideration.

The comments by these authors pertaining to “same stress, nervousness, and muscular tension” additionally suggests an involvement of the sympathetic nervous system. Hubbard and Berkoff (12) from the Department of Neurosciences, University of California, San Diego (my alma mater), were able to show that increased sympathetic tone will cause increased muscle tension. This will also have biomechanical therapeutic implications, below.

- In April 2003, Drs. Bjorne and Agerberg published another study in the Journal of Craniomandibular Practice (Cranio) titled (13):

Reduction in sick leave and costs to society of patients

with Meniere’s disease after treatment of temporomandibular and

cervical spine disorders: a controlled six-year cost-benefit study

In this study the authors conclude:

The costs to society for sick leave and disability pension due to Meniere’s disease are substantial compared to the same costs for control subjects from the population.

The present study also shows that the coordinated treatment of the Meniere patients’ temporomandibular disorder and cervical spine disorders appears to substantially reduce the costs to society of sick leave due to the decrease in frequency and intensity of their symptoms of Meniere’s disease.

The benefit in reduced costs to society of days of sick leave are more than five times the treatment costs for the patients.

- In 2006, German physician A Reisshauer and colleagues published a study in the journal HNO titled (14):

Functional disturbances of the cervical spine in tinnitus

In this study, 189 patients with tinnitus, Meniere’s disease, and sudden hearing loss underwent manual therapeutic examination at the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation in the setting of an interdisciplinary program for the management of patients of the tinnitus daycare center and inpatients of the ENT department of the Charité Medical School.

In all patients, global and segmental joint mobility of the cervical spine, cervicothoracic junction, first rib, and craniomandibular system was assessed using standardized documentation. Muscle extensibility and trigger points were determined for the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the descending part of the trapezius muscle, the levator muscle of the scapula, and the masseter muscle.

Results showed that patients with tinnitus have characteristic and specific patterns of abnormalities in the joints and paravertebral muscles. The dominant finding is an overall impairment of cervical spine mobility, to which various factors contribute. These include disturbed function of segmental joints of the head and the cervicothoracic junction as well as muscular imbalances of the shoulder and neck muscles.

This study adds support for the evidence that cervical spine biomechanical function may be involved in the pathophysiology of Meniere’s disease.

- In 2007, Dr. Assar Bjorne published an article in the journal Progressive Brain Research, titled (15):

Assessment of temporomandibular

and cervical spine disorders in tinnitus patients

In this study, Dr. Bjorne reviews his prior work on Meniere’s disease, stating:

Many of such patients had also symptoms of cervical spine disorders, head, neck and shoulder pain, and limitations in side bending and rotation were also frequent complaints. One-third of these patients could influence tinnitus by jaw movements and 75% could trigger vertigo by head or neck movements. Treatment of jaw and neck disorders in 24 patients with Meniere’s disease had a beneficial effect on not only their episodic vertigo but also on their tinnitus and aural fullness. At the 3-year follow-up, intensity of all symptoms were significantly reduced.

- Also in 2007, Burkhard Franz and Colin Anderson from the Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology of the University of Melbourne and the Tinnitus Research and Balance Clinic, Victoria, Australia, published an article in the International Tinnitus Journal, titled (16):

The potential Role of Joint Injury and Eustachian Tube Dysfunction

in the Genesis of Secondary Meniere’s Disease

In the article abstract, these authors note:

Meniere’s disease not only includes the symptom complex consisting of attacks of vertigo, low-frequency hearing loss, and tinnitus but also comprises symptoms related to the eustachian tube, the upper cervical spine, the temporomandibular joints, and the autonomic nervous system.

Clinical practice also shows that treating disorders of the upper cervical spine and temporomandibular joints can lessen Meniere’s disease symptoms, suggesting a relationship.

Similarly, stellate ganglion blocks can be beneficial in controlling Meniere’s disease symptoms, highlighting the influence of the autonomic nervous system.

Thus, contrasting symptoms associated with the eustachian tube, the upper cervical spine, the temporomandibular joints, and the autonomic nervous system relate to Meniere’s disease.

We made an attempt in this study to describe a hypothetical reflex pathway that links joint injury and the autonomic nervous system, where eustachian tube function is under their influence and is the critical link.

In this hypothetical reflex pathway, irritation of facet joints can first lead to an activated anterior cervical sympathetic system via an independent pathway in the mediolateral cell column; it can simultaneously lead to an axon reflex involving nociceptive neurons, resulting in neurogenic inflammation and the prospect of a eustachian tube dysfunction.

The eustachian tube dysfunction is responsible for a disturbed middle ear-inner ear pressure relationship, circumstances that have the potential to develop into secondary Meniere’s disease.

These authors also note that it has been observed for about five decades that disorders and/or injury of the cervical spine is involved in Meniere’s disease. They propose the following:

A disorder of the upper cervical spine or of the temporomandibular joint will initiate a reflex to the mandibular branch cranial nerve V motor which may result in ineffective Eustachian tube opening secondary to hyperactivity of the tensor veli palatini. The eustachian tube has “quite a remarkable representation of sensory neurons” that can be activated through the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve that innervates the temporomandibular joint and upper cervical facet joints.

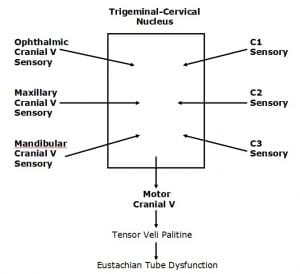

Both the sensory divisions of the Trigeminal nerve (cranial V) and the sensory branches of C1-C2-C3 converge in the trigeminal-cervical nucleus of the medulla and upper cervical cord.

Both can subsequently activate the motor division of the Trigeminal nerve (cranial V), which innervates the tensor tympani muscle, affecting eustachian tube function.

The inner ear receives neurological input from the trigeminal and sympathetic nerves through the tympanic plexus. Sympathetic hyperactivity leads to dysfunction in the eustachian tube which could influence middle ear pressure relationships.

These authors state:

An upper cervical facet joint disorder (or temporomandibular joint disorder) could simultaneously release inflammatory mediators in the eustachian tube via an axon reflex and activate the anterior cervical sympathetic system, the latter enhancing neurogenic inflammation in the eustachian tube resulting in reduced middle-ear ventilation. This imbalance of a middle ear—inner ear pressure relationship has the potential to develop into secondary Meniere’s disease.

Unquestionably, the upper cervical spine, the temporomandibular joints, the eustachian tube, and the autonomic nervous system can contribute to the global symptom complex of Meniere’s disease.

- In 2008, Michael Burcon, DC, published a case study of ten patients with Meniere’s disease who were analyzed and treated chiropractically. The study was published in the Journal of Vertebral Subluxation Research and titled (17):

Upper Cervical Protocol to Reduce Vertebral Subluxation

in Ten Subjects with Meniere’s: A Case Series

In this study, all patients had a history of cervical trauma, particularly that of a prior whiplash trauma. All patients showed biomechanical dysfunctions of the upper cervical spine. All but one patient showed significant improvement of clinical symptoms following specific spinal adjusting (manipulation) of the upper cervical spine. Dr. Burcon concluded:

It is possible that the true cause of Meniere’s disease is not only endolymphatic hydrops as theorized, but that vertebral subluxation [neurobiomechanical lesions of the upper cervical spine] plays a role.

In conclusion, Meniere’s disease is debilitating and chronic. The discussion presented here shows that there exists a relationship between Meniere’s disease and the neurobiomechanical function of the upper cervical spine and the temporomandibular joints. It is documented that both upper cervical and temporomandibular afferents reflex into the trigeminal-cervical nucleus, altering the motor control of the tensor veli palitini muscle, which in turn adversely influences the proper function of the Eustachian tube. Both upper cervical and temporomandibular afferents also reflex into the sympathetic neuronal pools in the upper thoracic spinal cord which can influence the tone of the tensor veli palitine muscles an well as alter the visceral function of the Eustachian tube. Both mechanisms may be related to Meniere’s disease. It is suggested that all patients suffering from Meniere’s disease have assessment and treatment of the cervical spine and temporomandibular joints as a component of their overall management. The studies presented here show that such an approach is often effective in improvement of signs and symptoms, and improvement in quality of life.

REFERENCES

- Baloh RW, Honrubia V, “Endolymphatic Hydrops (Meniere’s Syndrome),” Chapter 10, in Clinical Neurophysiology of the Vestibular System, Third Edition, Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Parker,HL. Clinical Studies in Neurology. Charles C Thomas Publisher, second edition, 1956.

- Lewit K. Meniere’s Disease and the Cervical Spine. Rev Czech Med. 1961;7:129-39.

- Braaf MM, Rosner S. Meniere-like Syndrome Following Whiplash Injury of the Neck. Journal of Trauma. September 1962, pp. 494-501.

- Junghanns H; Schmorl’s and Junghanns’ The Human Spine in Health and Disease; Grune & Stratton; 1971.

- Vernon H. Upper Cervical Syndrome. Williams & Wilkins, 1998.

- Bjorne A, Agerberg G. Craniomandibular disorders in patients with Menière’s disease: a controlled study. J Orofac Pain. 1996 Winter;10(1):28-37.

- Kaplan A, Assael L, Temporomandibular Disorders, Diagnosis and Treatment, WB Saunders Company, 1991.

- Bjorne A, Berven A, Agerberg G. Cervical signs and symptoms in patients with Meniere’s disease: a controlled study. Cranio. 1998 Jul;16(3):194-202.

- Franz B, Altidis P, Altidis B, Collis-Brown G. The cervicogenic otoocular syndrome: a suspected forerunner of Ménière’s disease. International Tinnitus Journal. 1999;5(2):125-30.

- Bjorne A, Agerberg G. Symptom relief after treatment of temporomandibular and cervical spine disorders in patients with Meniere’s disease: a three-year follow-up. Cranio. 2003 Jan;21(1):50-60.

- Hubbard DR, Berkoff GM. Myofascial trigger points show spontaneous needle EMG activity. Spine, October 1, 1993;18(13):1803-7.

- Bjorne A, Agerberg G. Reduction in sick leave and costs to society of patients with Meniere’s disease after treatment of temporomandibular and cervical spine disorders: a controlled six-year cost-benefit study. Cranio. 2003 Apr;21(2):136-43.

- Reisshauer A, Mathiske-Schmidt K, Küchler I, Umland G, Klapp BF, Mazurek B. Functional disturbances of the cervical spine in tinnitus. HNO. 2006 Feb;54(2):125-31.

- Bjorne A. Assessment of temporomandibular and cervical spine disorders in tinnitus patients. Prog Brain Res. 2007;166:215-9.

- Franz B, Anderson C. The potential Role of Joint Injury and Eustachian Tube Dysfunction in the Genesis of Secondary Meniere’s Disease. International Tinnitus Journal, 2007, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp. 132-137.

- Burcon M. Upper Cervical Protocol to Reduce Vertebral Subluxation in Ten Subjects with Menieres: A Case Series. Journal of Vertebral Subluxation Research, June 2, 2008, pp 1-8.