Perhaps the best reference book pertaining to the jaw is the 1991 text by Andrew Kaplan, DMD and Leon Assael, DMD, titled Temporomandibular Disorders, Diagnosis and Treatment (1).

This book has 31 distinguished contributing authors, 35 chapters, and 754 pages.

Dr. Kaplan’s credentials include:

Director, Temporomandibular Disorder/Facial Pain Clinic, The Mount Sinai HospitalAssistant Clinical Professor, The Mount Sinai Hospital

Coordinator, Department of Dentistry, The Mount Sinai Hospital Clinical Instructor, Department of Medicine, Hospital Division, New York University

Dr. Assael’s credentials include:

Associate Professor and Residency Program Director, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, School of Dental Medicine Associate Professor of Surgery, School of Medicine, University of Connecticut

Associate Chief of Staff, John Dempsey Hospital

Attending Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon, Hartford Hospital, Hartford, Connecticut

Dr. Kaplan and Assael’s text discusses scenarios whereby temporomandibular jointa disorders may occur as a consequence of direct mechanisms or as a consequence of altered neurobiomechanical function of the cervical spine. Their list of direct mechanisms of temporomandibular disorders includes:

- A blow to the chin

- Yawning

- Unexpectedly biting down on a hard substance while chewing soft food

- Whiplash trauma

- A fall from a bicycle

- A non-impact jolting of the mandible, like a “banana-peel” fall on to the back

- Iatrogenic dental procedures

- Epileptic seizures

- Teeth clenching during childbirth—labor and delivery

- Frequent gum chewing

- Frequent nail biting

- Frequent resting of the jaw on one’s hand

- Frequent lip biting

- Frequent bruxism

- Frequent clenching

- Postural microtrauma during scuba diving, playing the violin, etc.

- Prolonged forward head posture

Drs. Kaplan and Assael note a delay of symptomatology, or latency, is often observed in patients with temporomandibular disorders. They state:

“Temporomandibular joint pain may develop weeks or months after initial trauma.”

They note in the case of temporomandibular pain as a consequence of forward head posture that symptoms may be delayed for as long as a “few years.”

Supporting Drs. Kaplan and Assael’s comment on temporomandibular joint delay of symptoms is a recent (2007) prospective study published in the Journal of the American Dental Association, titled (2):

Delayed temporomandibular joint pain and dysfunction induced by whiplash trauma: a controlled prospective study

In this study, the authors studied 60 consecutive patients who had neck symptoms after whiplash trauma and were seen at a hospital emergency department. They followed up 59 subjects one full year later. At the initial examination and at follow-up, each subject completed a self-administered questionnaire, followed by a comprehensive interview. Fifty-three frequency-matched control subjects followed the same protocol concurrently. The authors found that the incidence of new symptoms of temporomandibular joint pain, dysfunction or both between the initial examination and follow-up was five times higher in subjects (34 percent) than in control subjects (7 percent).

At the follow-up evaluation, 20 percent of all subjects reported that temporomandibular joint symptoms were their main complaint. These authors concluded that one in three people who are exposed to whiplash trauma are at risk of developing delayed temporomandibular joint symptoms that may require clinical management.

A summary of the initial and final (one year later) evaluation is as follows:

| Initial Evaluation Injured Patients | Initial Evaluation Control Subjects | Final Evaluation Injured Patients | Final Evaluation Control Subjects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disturbed Sleep | 44% | 2% | 41% | 0% |

| Symptoms Negatively Impacting Daily Life | 53% | 2% | 41% | 4% |

| TMJ Symptoms as Main Complaint | 5% | 2% | 19% | 3% |

Additional findings from this study include:

1) Temporomandibular joint symptoms were consistently located “at the site immediately in front of the ear canal and tragus.”

2) Typical temporomandibular joint symptoms presented were clicking, crepitations, transient locking, locking with restricted mandibular movements, mandibular deflection and pain.

3) This study shows that “delayed temporomandibular joint symptoms frequently appear after whiplash trauma.”

4) “One in five subjects reported that temporomandibular joint symptoms were their main complaint one full year after the accident. This was quadruple the number of subjects reporting temporomandibular joint symptoms as their main complaint directly after the accident, and the increase was found in female subjects.”

5) At follow-up, “one in three subjects reported having temporomandibular joint pain, which was five times more frequent than in control subjects.”

6) “The majority of subjects with temporomandibular joint symptoms as their main complaint at follow-up reported the onset of new symptoms that were consistent with painful non-reducing temporomandibular joint disk displacement.”

7) “One in three people who are exposed to whiplash trauma, which induces neck symptoms, is at risk of developing delayed TMJ pain and dysfunction with onset during the year after the accident.”

Consistent with this article (2), of the direct mechanisms of temporomandibular disorders, significant information is published concerning whiplash trauma as an etiology. Most reference books on whiplash trauma have sections or entire chapters pertaining to temporomandibular disorders (3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8). In fact, there is a 1992 text titled (9):

Whiplash And Temporomandibular Disorders

The basic theme of these reference books is that there exists the potential for temporomandibular joint injury during whiplash because the mandible has a different inertia that the rest of the skull. Therefore, the temporomandibular joint injury from whiplash trauma is an inertial injury, there often being no direct blow to the jaw.

A recent article has quantified the risk of developing painful jaw movements following whiplash trauma and comparing such risk to a control population (10). It was published in 2007 in the Journal of the American Dental Association, and titled:

Reduced or painful jaw movement after collision-related injuries

A large population-based study

In this study, all adults filing collision-related personal injury claims during an 18-month period in Saskatchewan, Canada, were evaluated via questionnaire to determine demographic characteristics, pre-collision health (including jaw pain), collision parameters and collision-related symptoms, including reduced and/or painful jaw movement and injury-related neck pain. The authors excluded patients who were hospitalized for more than two days and those who sustained injuries as a pedestrian, bicyclist or motorcyclist. The authors also excluded those who had had jaw pain before the collision.

The incidence of reduced and/or painful jaw movement was 15.8% in subjects with whiplash injuries. The incidence of reduced and/or painful jaw movement was 4.7% in subjects without whiplash injuries. Therefore, those with whiplash injuries were 336% more likely to have reduced and/or painful jaw movement than those without whiplash injuries.

These authors concluded that reduced or painful jaw movement is more common in whiplash-injured persons than in those with other collision-related injuries. Reduced or painful jaw movement is an important aspect of whiplash injuries. These authors make the following comments:

“Temporomandibular Disorder consists of varying combinations of jaw pain or dysfunction, headache, dizziness and auditory disturbance, and is considered to be clinically relevant after collision-related injuries, especially in people with whiplash injuries.”

“After a motor vehicle collision resulting in whiplash injuries, 17.4% of people reported experiencing jaw pain in the collision; among those with no history of jaw pain, 15.8% reported experiencing jaw problems after the collision.” This “suggests that whiplash injuries in a motor vehicle collision are associated with temporomandibular disorder.”

“We found that reduced and/or painful jaw movement was more common after a collision-related whiplash injury than after other collision-related injuries.”

Very recently (2008), The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice published an article qualifying the nature of the temporomandibular joint disorders seen in a clinical setting. The article is titled (11):

Temporomandibular Joint Internal Derangement:

Association with Headache, Joint Effusion, Bruxism, and Joint Pain

In this study, the authors assessed the correlation of temporomandibular joint internal derangement in patients with the presence of headache, bruxism, and joint pain using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). They evaluated 42 symptomatic patients and compared them to 16 asymptomatic controls.

These authors found that common temporomandibular disorder complaints include:

Headache

Jaw ache

Earache

Facial pain

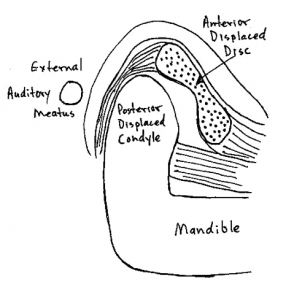

Importantly, they found that the most common type of temporomandibular joint dysfunction involves alterations of the condyle-disk relationship. The most common condyle-disk derangement of the temporomandibular joint is anterior disc displacement. Temporomandibular joint disc displacement is associated with joint effusion. They state:

“Temporomandibular joint effusion represents an inflammatory response to a dysfunctional disk-condyle relationship,” and this is associated with pain and headache.

“Patients with unexplained headaches should be considered for evaluation of the presence of internal derangement and inflammation of the temporomandibular joint.”

This article suggests the following pathophysiological model:

Abnormal mechanical stresses within the temporomandibular joint result in accumulation of irritating agents in the tissue fluid and inflammatory changes in the synovial membrane leading to subsequent joint effusion, temporomandibular joint pain, and headache.

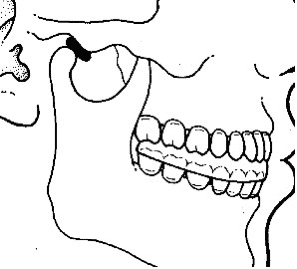

This would suggest that a reasonable approach to management would start with effective treatment of the abnormal mechanical stresses of the temporomandibular joint. As noted above, the primary abnormal mechanical stress is an anterior displacement of the temporomandibular joint disc. The 1991 book by Andrew Kaplan and Leon Assael above (1), shows and discusses how the temporomandibular joint anterior disk displacement can be manipulated with an inferior/anterior line of drive in an effort at repositioning the disk. Please refer to the following illustrations:

The Most common Temporomandibular Dysfunction:

Posterior Condyle Displacement / Anterior Disc Displacement

Normal temporomandibular disc alignment

Anterior temporomandibular disc displacement

Reductive adjustment of the temporomandibular joint. The mandible is manually distracted anterior and inferior while the skull is stabilized “in an effort to manually reduce the displaced disc.” The adjustment involves controlled distraction only, there is no thrust.(After Kaplan and Assael)

Cervical Spine and Temporomandibular Relationships

It is increasingly being accepted that disorders of the cervical spine can cause temporomandibular disorders, even in the absence of direct injury or stress to the temporomandibular joint. In such cases, although the symptoms may be attributed to the jaw, the treatment is to the cervical spine.

In 1998, the journal Clinical Oral Investigations, published a study titled (12):

Correlation Between Cervical Spine and Temporomandibular Disorders

These authors evaluated 31 consecutive patients with symptoms of temporomandibular disorders and 30 controls with a standardised clinical examination of the masticatory system, evaluating range of motion of the mandible, temporomandibular joint function and pain of the temporomandibular joints and masticatory muscles. Afterwards subjects were referred for clinical examination of the cervical spine, evaluating segmental limitations, tender points upon palpation of the muscles, hyperalgesia and hypermobility.

The results indicated that segmental limitations (especially at the Occiput-C3 levels) and tender points (especially in the m. sternocleidomastoideus and m. trapezius) are significantly more present in patients than in controls.

These authors concluded that there are neuroanatomical interconnections and neurophysiological relationships between the cervical spine and the jaw. Sensory information from the cervical spine converges with trigeminal afferents in the trigeminal spinal nucleus; these trigeminal fibers descend at least to C2-C3 and perhaps as low as C6. Therefore, the “temporomandibular system and the cervical spine function as a single entity.”

Additional support for a cervical spine and temporomandibular functional relationship was published in 2004 in the European Journal of Oral Sciences and titled (13):

Deranged jaw–neck motor control in whiplash-associated disorders

These authors note that jaw movements are the result of activation of jaw as well as neck muscles, leading to simultaneous movements in the temporomandibular, atlanto-occipital and cervical spine joints. Therefore, injury to the neck would disturb natural jaw function. Anatomical, biomechanical, neuroanatomical, neurophysiological and clinical studies indicate that the mandibular and the craniocervical regions are functionally linked. Natural jaw activities require a healthy state of both the mandibular and the head–neck motor systems. Natural jaw actions require a healthy state not only of the temporomandibular joint but also of the atlanto-occipital and the cervical spine joints. Head-neck trauma can be an etiological factor behind temporomandibular disorders. Neck injury from whiplash is associated with deranged control of mandibular movements which compromise jaw function.

These authors are indicating that the pain in the jaw following whiplash injury is not primarily from direct trauma to the jaw. Rather, they are presenting evidence that supports that whiplash injuries to the cervical spine alter the normal function of the jaw. Injury to the upper cervical spine causes a reflex to the muscle spindles of the jaw muscles, which are extensive. The jaw muscles contract, resulting in more dysfunction and pain. These authors are using a neurological model rather than an orthopedic model for temporomandibular dysfunction following whiplash trauma.

Additional support for a cervical spine and temporomandibular functional relationship was published very recently (2008) in the Swedish Dental Journal and titled (14):

Impaired jaw function and eating difficulties

in whiplash-associated disorders

These authors evaluated 50 whiplash-injured patients with pain and dysfunction in the jaw-face region and 50 healthy age- and sex-matched controls without any history of neck injury. For the whiplash-injured group, there were significant differences in jaw pain and dysfunction and eating behavior after the accident. Both the healthy and the whiplash-injured group reported no or few jaw-face symptoms before the accident. The whiplash-injured patients after the accident reported pain and dysfunction during mouth opening, biting, chewing, swallowing and yawning and felt fatigue, stiffness and numbness in the jaw-face region. In addition, a majority also reported avoiding tough food and big pieces of food, and taking breaks during meals.

These authors note that jaw opening-closing movements are the result of coordinated activation of both jaw and neck muscles, with simultaneous movements in the temporomandibular, atlanto-occipital and cervical spine joints. Consequently, pain or dysfunction in any of the three joint systems involved could impair jaw activities.

These authors concluded that examination of jaw function should be recommended as part of the assessment and rehabilitation of whiplash-injured patients.

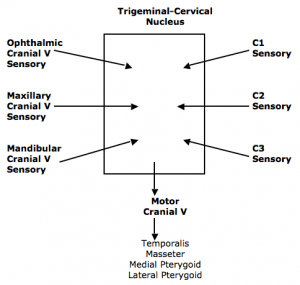

These cervical spine / temporomandibular relationships are summarized in the following graph:

Both the sensory divisions of the Trigeminal nerve (cranial V) and the sensory branches of C1-C2-C3 converge in the trigeminal-cervical nucleus of the medulla and upper cervical cord.

Both can subsequently activate the motor division of the Trigeminal nerve (cranial V), which innervates the temporalis, masseter, medial and lateral pterygoid muscles.

Since all four of these muscles cross the temporomandibular joint, muscular imbalance, temporomandibular joint imbalance, abnormal joint biomechanical stress, inflammation and pain can result.

In summary, in patients with upper neck, jaw, face or head pain, both the cervical spine and temporomandibular joints should be evaluated. The commonly found anterior disc displacement of the temporomandibular joint can be carefully manipulated back into proper position with a distraction maneuver by those who are trained in manual therapy. Primary dysfunction of the joints of the upper cervical spine can cause secondary dysfunction of the temporomandibular joints; in such cases, treatment is to the dysfunctional joints of the cervical spine.

Dan Murphy, DC

REFERENCES

1) Andrew Kaplan, DMD and Leon Assael, DMD, Temporomandibular

Disorders, Diagnosis and Treatment, WB Saunders Company, 1991.

2) Salé H, Isberg A; Delayed temporomandibular joint pain and dysfunction induced by whiplash trauma: a controlled prospective study; Journal of the American Dental Association; August 2007;138(8): pp. 1084-91.

3) Steven Foreman, Arthur Croft, Whiplash Injuries, The Acceleration / Deceleration Syndrome, Williams & Wilkins, 1988.

4) C. David Tollison, John Sattertwaite, Painful Cervical Trauma, Diagnosis and Rehabilitative Treatment of Neuromusculoskeletal Injuries, Williams & Wilkins, 1992.

5) Gerald Malanga, Cervical Flexion-Extension / Whiplash Injures, Spine State of the Art Reviews, 1998.

6) Bernard Swerdlow, Whiplash and Related Headaches, CRC Press, 1999.

7) Gerald Malanga, Scott Nadler, Whiplash, Hanley & Belfus, 2002.

8) Lawrence Nordhoff, Motor Vehicle Collision Injuries, Biomechanics, Diagnosis, and Management, Second Edition, Jones and Bartlett publishers, 2005.

9) Dennis Steigerwald, Whiplash And Temporomandibular Disorders, Keiser Publishing, 1991.

10) Linda J. Carroll, Robert Ferrari, J. David Cassidy; Reduced or painful jaw movement after collision-related injuries: A large population-based study; Journal of the American Dental Association January 2007, Vol. 138, No. 1, pp. 86-93.

11) Costa ALF, D’Abreu A, Cendes F; Temporomandibular Joint Internal Derangement: Association with Headache, Joint Effusion, Bruxism, and Joint Pain; The Journal of Contemporary Dental Practice; Volume 9, No. 6, September 1, 2008, pp. 9-16.

12) A. De Laat, H. Meuleman, A. Stevens, G. Verbeke; Correlation Between Cervical Spine and Temporomandibular Disorders; Clinical Oral Investigations; 1998, 2: pp. 54-57.

13) Per-Olof Eriksson, Hamayun Zafar, Birgitta Haggman-Henrikson; Deranged jaw–neck motor control in whiplash-associated disorders; European Journal of Oral Sciences, February, 2004; 112: 25–32.

14) Grönqvist J, Häggman-Henrikson B, Eriksson PO; Impaired jaw function and eating difficulties in whiplash-associated disorders; Swed Dent J. 2008;32(4):171-7.